|

Photo from the album of J. J.

Watson Excerpt

from “An

Anecdotal Life of Sir John Macdonald”

by

E. B. Biggar Published

1891 About 1825, Hugh Macdonald gave up his

business in Kingston and moved up the Bay of Quinte, to a point about 15 or

20 miles west of Kingston. The scenery

of the Bay of Quinte is charming to the eye of a stranger. The long stretch of water which cuts off

Prince Edward county from the mainland, and makes it almost an island, is

free from the wild storms which beat upon the outer shores of the county; and

the stranger sailing up these pleasant waters sees peace and loveliness on

every hand. An ever varying panorama

is presented to the eye: here a quiet

bay, there a rocky bluff, again a reedy biyou,

beyond a shelving shore, and anon an opening where a reach of water, long and

winding, finds its way for miles and miles, making peninsula after peninsula

of always varying size and aspect. At

the present day these sylvan scenes are dotted with farm houses; and in

summer the yellow grain fields, richly laden apple orchards, fields of clover

or of buckwheat, whose creamy bloom exhales an odor more delightful than “all

the perfumes of Arabia,” checker the landscape over, but at that time the

shores, the distant hills, the rolling uplands and breezy heights were alike

clad with dense groves of maple, oak, hickory, ash and other kinds of

Canadian forest trees. At the root, as it were, of one of these

many tongues of land formed by the arms of the Bay of Quinte, was one of the

settlements of United Empire Loyalists – those people who, in the American

Revolution, “sacrificed their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor”

to maintain as a united empire Great Britain and her colonies. These settlers had been attracted by the beauty

of the scenery and the rich soil, and, at the time we speak of, had in this

particular neighborhood two small settlements, one around the village of

Adolphustown, and the other along Hay Bay on the other side of this tongue of

land. It was at Hay Bay that the

Macdonald family fixed their abode. It

stood by the side of the high road, about eighty feet from the water. The shore curved in gracefully from a far

point of land down towards the house, and the clear waters, whether ruffled

by the transient breeze, or in the calm of evening reflecting the distant

hills across the bay, must have been a delight and an inspiration to the lad

whose fortunes we are following. The writer visited the spot in the summer

of 1890. The waters of the bay,

whether from the sinking of the ground or the rising of the water level, had

encroached to within forty feet of the old homestead, while down on the

farther side of this little bay, two dwellings that formed part of the

homestead of Judge Fisher, their nearest neighbor, were now entirely

submerged. A pleasant breeze was

sending up to the shore little wavelets that chuckled gleefully under the

logs and limbs of fallen trees that lay along the water’s edge. From one of

these logs a solitary mud-turtle dropped off at our approach, and

pushed his way through the reeds. Lady

Macdonald, looking on the same scene a few years before, and noticing the

same turtle, or its companion, sitting on the same log, made this quaint

exclamation: -- “There!

There is the very old turtle my husband used to shy stones at when he

was a boy.” But where is the homestead? It is gone. Its

dwellings down, its tenants passed away. A crop of peas was ripening in the field

which had enclosed the house. No trace

of it was to be seen, till, going to an uneven spot of ground, the

remains of the old foundation were to be made out, quite overgrown with

pea-vines, weeds and grass. Here were

the remains of the old cellar kitchen, that opened out towards the bay, and

which was still but partially filled up with deposits of leaves and the

washing so years of rains. A red

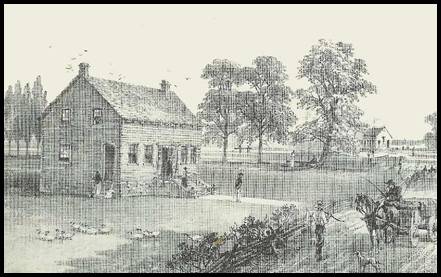

willow had grown up in the middle of the cellar. It was a clapboarded wooden house, painted

red, with a wooden shingled roof, the west half of the place being used as a

store and the east as a dwelling. The

dimensions of the whole were 30 x 36 ft.

Though the house was long since burned to the ground, a very accurate

re-construction of it in print, reproduced here, was made by Mr. Canniff

Haight for his book, “Country Life in Canada Fifty Years Ago.” Mr. Haight having often seen it before it

had fallen. It was not built for the Macdonalds, but had been occupied by a man named Dettler. A bumble-bee droned over the catnip that

grew along the tumbled stones of the foundation, and its dreamy noise, and

the clucking of the waters lulled the mind into a reflective mood, and set

one to dreaming over the wonderful career and the complex changes that were

wrought out in the life of the boy who played about this ruined wall and

paddled in this limpid water hard by.

These reflections were disturbed by a “caw caw” from one of the poplar

trees that still skirted the shore, and looking up we beheld a crow gazing

down in serious reflection on the scene.

Ah! Grip! You here now, and were you here then? You, whose life must have spanned over the

century, did you croak or prophesy at the home-coming of the school-boy who

was to sway the destinies of Canada?

And is this shattered tenement a type of the end of all human

glory? This much, old Grip, is

certain: Within a year the genius that

took thy name was never more to excite the mirth of thousands with new

variations of those playful sketches of the living face that looked up into

his mother’s, sitting before this kitchen door! AT SCHOOL AT ADOLPHUSTOWN The years at Adolphustown were chiefly

spent at school, Johnny for a portion of the time being sent back to

Kingston. The wiry lad, with his

sisters, Margaret and Louise, walked night and morning from Hay Bay to the

school at Adolphustown, a distance of three miles. The school house was a little wooden

structure, built by the original settlers, the U. E. Loyalists. Though the only one in the township, it was

but sixteen feet long or thereabouts, with two windows on each side, filled

with seven by eight inch window panes.

The old school is now used as a granary, and near to it there still

stands the oak tree- now grown to a patriarchal size – upon whose limb the

boy used to swing with his sisters and their companions. There was but one board desk in the school

house, and that ran round three sides of the room. The teacher’s desk was at the vacant end,

and a pail of water in the corner was about the only other piece of furniture

in this temple of learning, which was presided over by a crabbed old

Scotchman known as Old Hughes. Hughes

had an adroit method of taking a boy by the collar and giving him a lift off

his feet and a whack at the same time.

The skill and celerity with which he did this was very interesting to

all the boys, except the subject of the operation, and Johnny must often have

enjoyed the exhibition, though he had no love for the chief performer, upon

whom he played more than one sly trick.

His school mates of this early day describe Johnny Macdonald as thin

and spindly and pale, and his long and lumpy nose gave him such a peculiar

appearance, that some of the girls called him “ugly John Macdonald.” One of them says he did not show any marked

cleverness till later on, when he had got into the study of mathematics. He was not fond of athletics, or of

hunting, or sport, although he was very nimble and was a fleet runner. He delighted, like most boys in the country, to run barefoot in summer, and

often referred in after years, in his speeches, to this boyish pleasure. He was a good dancer, however, and was

rather fond of the diversion. He also

learned to skate in these days, and a school-mate, Mr. John J. Watson (of

whom Sir John never in after years spoke without giving him the school boy

title of “John Joe” , relates that one day, while a group of the boys were

skating, he tripped up Johnny, who was a poor skater. “What did you do that for?” demanded

Johnny, as he scramble to his feet. “Because I couldn’t help it, when I saw

such drumsticks as yours on ice.” Johnny made a dash after John Joe, but

John Joe was a fleet skater, and sailed easily to a safe distance. “I’ll visit you for this,” exclaimed

Johnny, pointing the finger of vengeance at John Joe, and it was expected

that John Joe would suffer for it afterwards.

He did not, though for a time afterwards Johnny seemed to lose respect

for him. As a boy, John Macdonald was considered by

many to be of a vindictive disposition and possessed of a violent

temper. He certainly was a passionate boy, but if he

ever possessed any vindictiveness, he must early have seen its danger, and

learned to control both it a and his temper.

His after career shows that in his dealings with his fellows his

self-control increased with his years.

Things that were put down by companions to vindictiveness might have

had no worse a motive than the boy’s inherent love of fun and mischief. On one occasion, when they lived at Hay

Bay, his sister Louise, and her companion, “Getty” Allen, got into the boat,

but forgot their oars, when Johnny, seeing the situation, shoved them out

into the bay. The two girls screamed

and scolded by turns, while Johnny laughed.

His mother came down, and with half-concealed enjoyment of the scene

exclaimed: - “You wicked boy, what did you do that

for? Suppose they upset?” “Then I would go and pull them in,” and he

waited for time and the evening breeze to waft them back to shore. The family were apparently in good

circumstances at this time, and were considered rather superior to their

neighbors around. They were usually

friendly and hospitable, but did not associate intimately with their

neighbors, except in the case of Judge Fisher’s family. Margaret and Louise were both fond of

music, and they had the only piano in this settlement. It had a small key-board, and legs almost

as thin as the legs of a table, like the instruments of that time, and had a

thin tone as well as thin legs.

However, the music had sufficient charm to draw young visitors from

many parts of the settlement to hear it.

The sisters, besides being able to play, sang very well together, in

part songs, the one taking soprano and the other alto. Before the family returned to reside in

Kingston, they lived for a year or two at a place then known as the Stone

Mills – now called Glenora – just below one of the natural curiosities of the

place, the “Lake on the Mountain.”

Here Mr. Macdonald leased a grist and carding mill, the running of

which was only an indifferent success. The old stone mill still exists, and

its situation on the side of the steep bluff is still as charming and almost

as wild as then. Game must have been

plentiful at that time, but our hero delighted in neither hunting nor

fishing, and the only hunting story handed down in this connection is one to

the effect that the Van Black boys, returning from a hunt, saw John coming up

the road. They had shot a crow, and in

order to have some fun, they braced this crow up on a stump in the adjoining

field, and lingered around till their young friend came up. One of them casually called attention to

the crow, when Johnny begged the gun “to have a whack at it.” He fired, but the crow never as much as

turned his head, and it was only the laughter that followed the second shot

that led the young marksman to suspect a joke had been played on him. William Canniff, of Toronto, gives a

reminiscence [Kingston Whig] of their life at the Stone Mills. Young Macdonald was always full of fun, and

delighted to play tricks upon his playmates.

On one occasion he aroused the displeasure of one of his

companions. The aggrieved boy, who was

larger than he caught Johnny in the flour mill, and having laid him

prostrate, proceeded to rub flour into the jet locks of his hair until it was

quite white. When released the victim went scampering down the hill,

laughing, and apparently appreciated the joke as much as the

perpetrator. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ At the election of 1882, Sir John ran for

Lennox, and during the campaign came to hold a meeting in Adolphustown, the

home of his boyhood. The ladies of the

village and neighborhood turned out and formed an equestrian procession to

escort him from the wharf to the house of Mr. J. J. Watson, one of his

schoolmates. The sight of these ladies

on horseback, and the crowds of people of all shades of political opinion who

had come to welcome this man, was unique in the social or political history

of the settlement. Sir John made himself at home in the house

of his early friend, with whom after many years of separation he sat down,

and, throwing aside all thought of politics or ambition, became a boy again,

and calling his friend, “John Joe”, and addressing Mrs. Watson as “Getty”,

talked with schoolboy animation of those bygone days, when they played tricks

with each other on the ice.

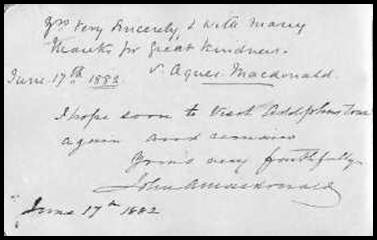

From

the autograph album of Mrs. J. J. Watson

John A. Macdonald and Agnes Macdonald visit Adolphustown June 17,

1882

Sir John A Macdonald’s Early Home From “Country Life in Canada Fifty Years Ago” By Canniff Haight Published 1885

|

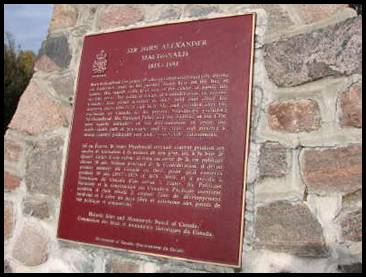

Monument

of Sir John A. Macdonald

South Shore Hay Bay, Adolphustown |

|

|

|

|

SIR JOHN ALEXANDER

MACDONALD

1815-1891 Born in

Scotland, the young Macdonald returned frequently during his

formative years to his parents’ home here on the Bay of Quinte. His superb skills kept him at the centre of

public life for fifty

years. The political genius of

Confederation, he became Canada’s

first prime minister in 1869, held that office for nineteen

years (1867-73 and 1878-91), and presided over the expansion

of Canada to its present boundaries excluding Newfoundland. His National Policy and the building of the

CPR were

equally indicative of his determination to resist the north-south

pull of geography and to create and preserve a strong

country politically free and commercially autonomous. Historic

Sites and Monuments board of Canada. |

|

|

View of Hay Bay Church on the Bay Shore Road Taken from the site of the Macdonald Monument 2006 |